Pattern Matching in Elixir

At the Flatiron School, our mission is to help people learn how to code. That means that as a member of the engineering team, my work reminds me almost every day of that important, universal truth: learning new stuff is hard.

Take learning to play a musical instrument, for example, like guitar. When you start, you have these lofty aspirations. You wanna be the next David Bowie. But when you’re first starting out, that dream is so, so far away. It takes a ton of hard work to get there, and it’s easy to get discouraged. Without some early wins, you might give up.

You need to learn that one cool riff that gets you hooked, where you don’t wanna put the guitar down, because now you’re in it.

It’s kinda the same thing with Elixir.

Lots of folks are excited about the language because of all the great things you get from using it - concurrency, fault tolerance, scalability - the hype list goes on and on. But none of these are things you can enjoy right away. You pretty much have to build and ship an entire app to production before you really start seeing any of this good stuff.

You need a quick win to keep you going, you need that cool riff. And for me, that cool riff was pattern matching.

So let’s break down what it is and why it’s so great.

The Match Operator

To understand pattern matching in Elixir, start by reframing the way you think about tying values to variables. Take the statement x = 1. You probably read that as “x equals 1”, where we’re assigning the value 1 to the variable x, right?

Welp, not in Elixir.

In that statement, the = is known as the “match operator”, and it’s not doing any assigning. Instead, it’s evaluating whether the value on the right matches the pattern on the left. If it’s a match, then the value is bound to the variable [1]. If not, then a MatchError is raised.

| x | = | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| pattern | match operator | value |

What does it mean to “match”? It means the value on the right matches the form and sequence of the pattern on the left.

Simple Examples

Let’s run through the basics of pattern matching with these simple examples below.

Binding on Match

x = 1

Here, the match evaluates to true, since anything on the right-hand-side will match on an empty variable, so the empty variable on the left is bound to the value on the right.

Match Without Binding

x = 1

1 = x

Both of these statements are valid expressions, and they also both match (!!!)

In the top expression, the match evaluates to true and the value is bound to the variable. In the bottom expression, the match evaluates to true, but nothing is bound, since variables can only be bound on the left side of the = match operator. For example, the statement 2 = y would throw a CompileError, since y is not defined.

Re-binding

x = 1

x = 2

If you pattern match on a bound variable, like x above, it will be rebound if it matches.

Pin Operator

x = 1

^x = 2

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: 2

If you don’t want the variable to be rebound on match, use the ^ pin operator. The pin operator prevents the variable from being rebound by forcing a strict match against its existing value.

Lists

iex(1)> [a, b, c] = [1, 2, 3]

iex(2)> a

#=> 1

iex(3)> b

#=> 2

iex(4)> c

#=> 3

We can pattern match on more complex data structures, like lists. Again, any left side variables will bound on a match.

List [head | tail] Format

iex(1)> [head | tail] = [1,2,3,4]

iex(2)> head

#=> 1

iex(3)> tail

#=> [2,3,4]

One cool thing you can do with lists is pattern match on the head and tail. Use the | syntax to bind the leftmost variable to the first element in the list and the remaining elements to the rightmost variable (these variables don’t have to be named head and tail; you can choose any names you want).

This syntax comes in handy when you have a list of elements you want to operate on one-by-one, since it allows you to recursively iterate over the list very cleanly and succinctly.

iex(1)> list = [2,3,4]

iex(2)> [1 | list]

#=> [1,2,3,4]

You can use this syntax to prepend elements to lists, too, if you’re feeling fancy.

iex(1)> [first | rest] = []

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: []

Watch out for empty lists, though. You’ll raise a MatchError if you use this syntax on an empty list, since there’s nothing to bind either variable to.

Match Errors

iex(1)> [x,y] = [4,5,6,7]

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: [4,5,6,7]

Keep in mind, the match will fail if you compare different size lists.

iex(1)> [foo, bar] = {:foo, :bar}

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: {:foo, :bar}

Matches also fail if you try to compare two different data structures, like a list and a tuple.

Tuples

iex(1)> {a, b, c} = {1,2,3}

iex(2)> a

#=> 1

iex(3)> b

#=> 2

iex(4)> c

#=> 3

Pattern matching with tuples operates much the same as with lists.

iex(1)> {:ok, message} = {:ok, "success"}

iex(2)> message

#=> "success"

iex(3)> {:ok, message} = {:error, "womp womp"}

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: {:error, "womp womp"}

One common pattern you’ll see in Elixir is functions returning tuples where the first element is an atom that signals status, like :ok or :error, and the second element is a string message. It’s leveraged in many core libraries, including File.read/1, Base.encode64/2 (and other encode + decode functions), Enumerable.count/1, etc.

_ Underscore Variable

iex(1)> { _, message } = {:ok, "success"}

iex(2)> message

#=> "success"

iex(3)> { _status, message } = {:error, "boom"}

iex(4)> message

#=> "boom"

For times when you want to pattern match but don’t care about capturing any values, you can use the _ underscore variable. This special reserved variable matches everything; it’s a perfect catch-all.

You can use it alone or as a named variable, like _ignore, which is a little more meaningful to folks reading your code.

iex(1)> {_, message} = {:ok, "success"}

iex(2)> _

#=> ** (CompileError) iex:2: unbound variable _

Just be aware that _ really truly is a throw-away variable, in that you can’t read from it. If you try, Elixir will throw a CompileError.

So what’s the big deal?

Maybe you’re not blown away by the examples above. Elixir has some nice syntactic sugar for pattern matching… but what’s so groundbreaking about that?

Let’s take a look at some practical real world applications.

Real World Examples

We’ll start with a problem that’s probably familiar to most web developers: displaying public-facing user “display names” based on user-inputted data.

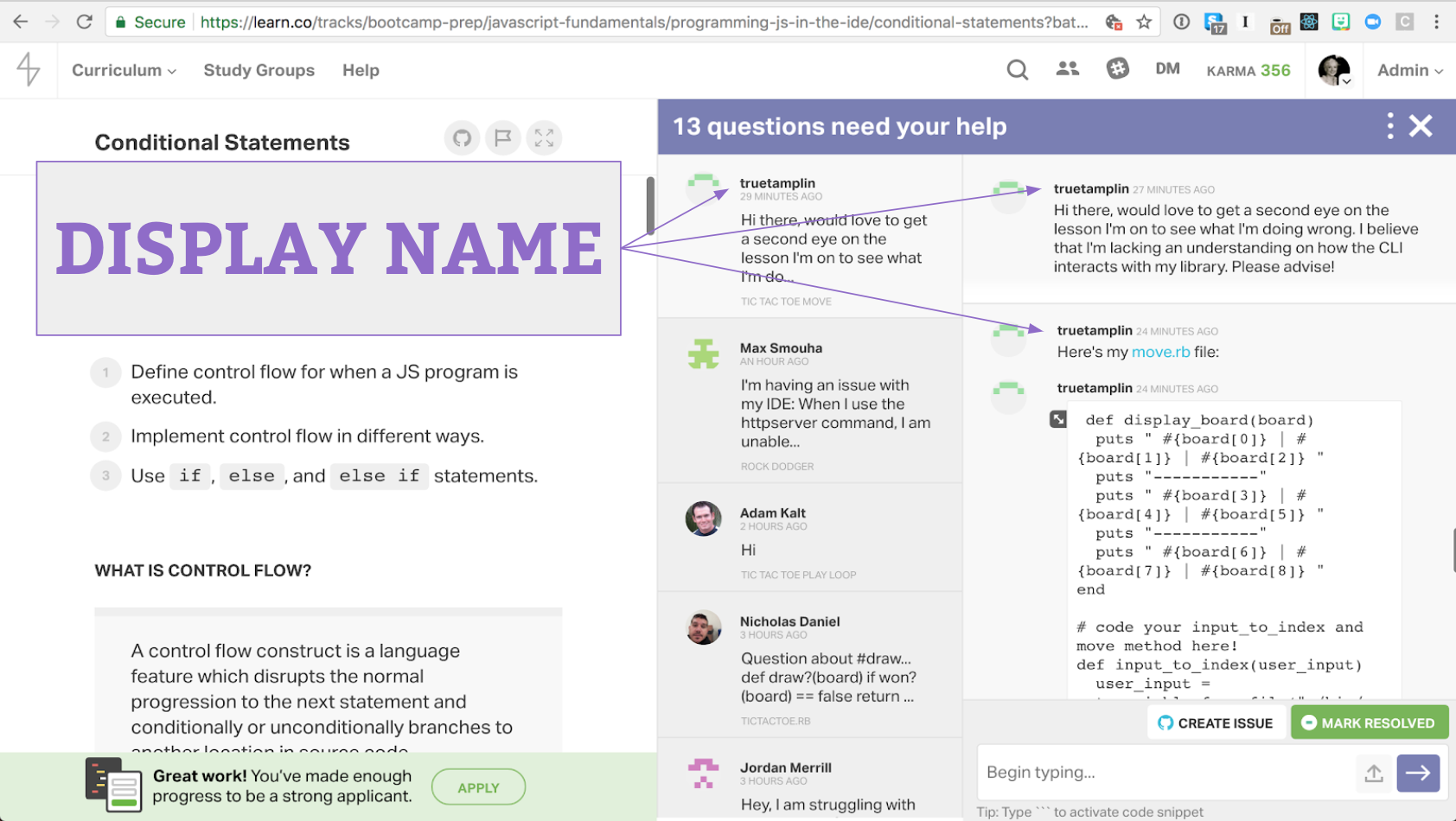

This was something I worked on recently in the Learn.co codebase. On our site, we like to encourage an active, friendly sense of community, so we display users’ names (built from information volunteered by the user) in lots of places across the site, including the Ask a Question chat feature.

Problem is, we don’t require users to give us their full name or even set a username, so when it comes to building a public-facing display name, there’s no guarantee that any identifying information - first name, last name, or username - is available. Additionally, all of this information is inputted manually by the user, and while we sanitize it to some degree before persisting, weird stuff can still get through.

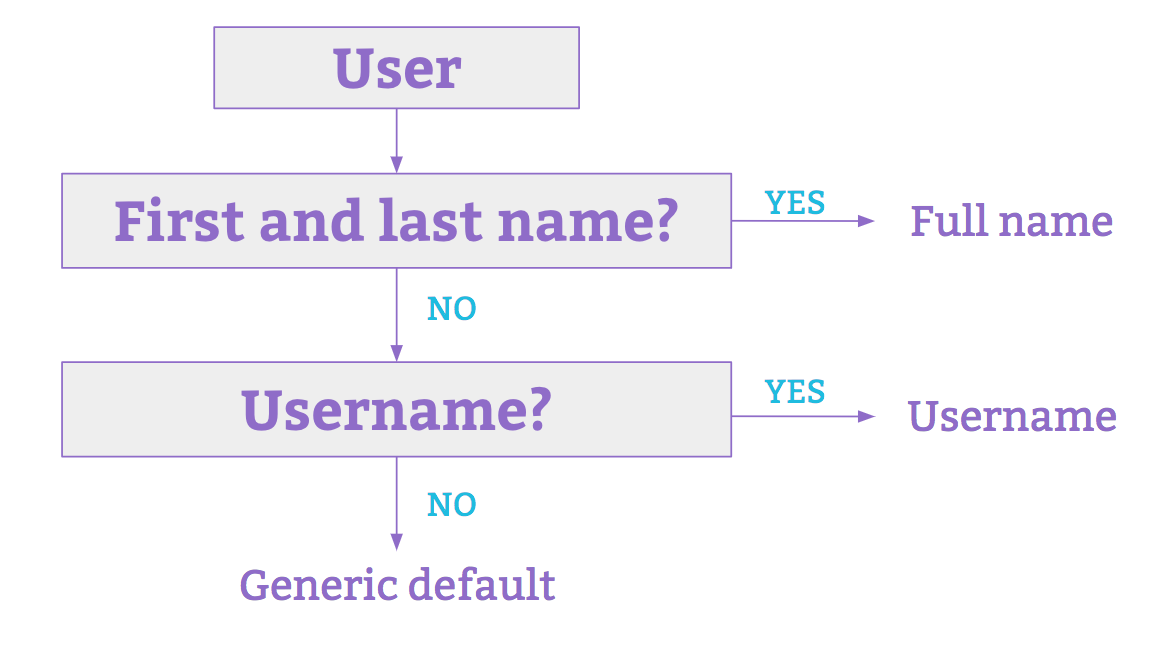

To address this problem, our product team developed the following requirements:

- If the user has provided their first and last name, display both together as their full name

- If we don’t have first or last name, check if the user has provided their username, and if yes, display the username in place of full name

- If we don’t have any of the above, display a reasonable generic default (here, we’ll just use “New User”)

How could we represent these conditions in code?

JavaScript Example

Writing that function in JavaScript might look something like this:*

export const displayName = (user) => {

if (user.firstName.length > 0) {

if (user.lastName.length > 0) {

return `${user.firstName} ${user.lastName}`.trim();

} else {

return `${user.firstName}`.trim();

}

} else if (user.username.length > 0) {

return user.username;

} else {

return 'New User';

}

}

* I realize these examples are somewhat contrived, but bear with me. They’re for illustrative purposes, not code review.

There’s a lot of things that make this function pretty hard to grok in one glance. First off, there’s JavaScript’s punctuation-heavy syntax, which can be a little rough on the eyes if you’ve been away from it for a little while. All the nested conditionals add complexity, too, as well as mental overload. Then additionally, we’re also doing some nil checking (via length) and throwing in some string sanitation for good measure. All-in-all, not super readable.

Ruby Example

If we switch to Ruby, a language praised for being “developer-friendly”, the situation doesn’t improve much.

def display_name(user)

if user.first_name.length > 0

if user.last_name.length > 0

"#{user.first_name} #{user.last_name}".strip

else

"#{user.first_name}".strip

end

elsif user.username.length > 0

user.username

else

'New User'

end

end

We still have our nested conditionals, and this long, “pointy” method decidedly does not pass the Sandi Metz “squint test”.

Elixir Example

Let’s see if we can fare any better with Elixir.

defmodule Account do

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}) do

String.trim("#{first} #{last}")

end

def display_name(%{username: username}), do: "#{username}"

def display_name(_), do: “New User”

end

Here, each conditional has been separated out into its own function clause. Unlike in other languages like Ruby, when we “overload” a function like this (e.g. make multiple function declarations with the same function name), we’re not overwriting the original function. Instead, these are known as multi-clause functions, and when you call a function that has several clauses, it’ll will try each clause (starting at the top of the file and moving down) until it finds one that matches.

You want to put your most specific clauses at the top, since those will match first. If you put something too general at the top, then it’ll match everything and none of the clauses below it will ever get hit. Luckily, Elixir is pretty cool and usually throws a warning if you make this mistake.

Multi-clause functions allow us to break our conditional logic into the smallest, atomic pieces, thereby keeping it isolated, encapsulated, and much more legible. It’s easy to tell at a glance what each of these function clauses is doing.

Handling the Un-Happy Path

But you might have noticed our Elixir example here has a bit of an unfair advantage. Most of the added complexity in the Ruby and JavaScript examples came from handling nil cases, and we’re not checking for those at all in the Elixir example - yet.

You might be tempted to throw a case statement into the first display_name/1 function clause (more on function name/arity syntax here). You’ll want to resist, though, because case statements are not The Elixir Way™.

Your next thought might be to try adding more higher-specificity clauses to the top of the file:

defmodule Account do

# Unwieldy nil checks

def display_name(%{first: nil, last: nil, username: nil}), do: display_name(%{})

def display_name(%{first: nil, last: nil, username: username}) do

display_name(%{username: username})

end

def display_name(%{first: nil, last: nil}), do: display_name(%{})

# Happy paths

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}), do: do_trim("#{first} #{last}")

def display_name(%{username: username}), do: "#{username}"

def display_name(_), do: “New User”

end

However, as you can see, this can get unwieldy fast. Today, we’re checking for nils in three fields, but what if requirements change? Given the possible permutations of all the possible fields on User we need to check against, you could end up with a super long, bloated module.

What to do instead? Elixir has our back here, too: guard clauses to the rescue.

Guard Clauses

defmodule Account do

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}) when not is_nil(first) do

String.trim("#{first} #{last}")

end

def display_name(%{username: username}) when not is_nil(username) do

"#{username}"

end

def display_name(_), do: "New User"

end

Elixir function declarations support guard clauses, which are a handy tool for augmenting pattern matching with more complex checks. Guard clauses are a nice way to match against more complex patterns without adding too much clutter to your functions. Only a handful of expressions are supported, and they’re meant to be short and sweet.

In the code block above, we’ve added not is_nil() guards to our first two clauses. Thanks to guard clauses, just adding a couple extra characters was all we needed to protect against nil values.

Custom Guard Clauses

Let’s throw one more curveball into the mix. There’s another case we need to guard against with display names, and that’s where a user has given us their full name, but it contains personal identifying information (PII).

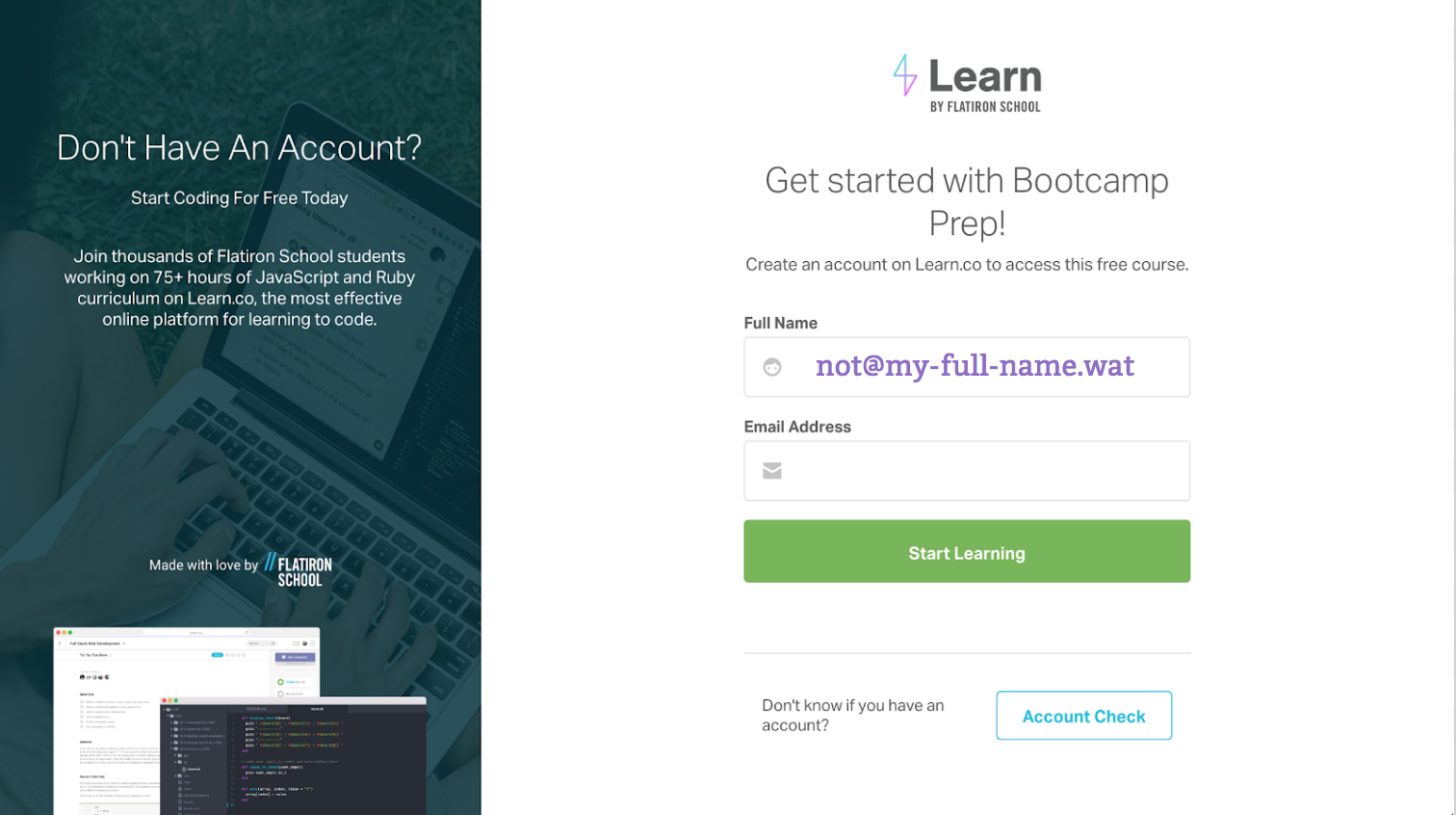

This situation actually used to happen not infrequently on Learn.co. For some reason on our public, free Bootcamp Prep course sign up page, users would often enter their email in the full name field.

Clearly, we needed to change something about this UI (and add more validations on user input, but that’s a separate blog post). However, since the bad data exists, we need to protect against it, and we can do so via some more complex pattern matching techniques.

So far, our display_name/1 function clauses look like this:

defmodule Account do

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}) when not is_nil(first) do

String.trim("#{first} #{last}")

end

def display_name(%{username: username}) when not is_nil(username) do

"#{username}"

end

def display_name(_), do: "New User"

end

You might be asking yourself, is now when we finally give up on this pattern matching thing and just add some logic inside the body of the first function clause? Surprise (not surprised) - the answer is NO. We haven’t exhausted Elixir’s pattern matching toolbox yet.

In addition to predefined guard clause expressions, Elixir also supports custom guard clauses. Now “custom” doesn’t mean you can throw any function in there; custom guard clauses still have to built from the limited list of allowed expressions. But they’re still super handy for keeping things DRY and simple.

You can create custom guards with macros, but the docs recommend defining them with defguard or defguardp because those perform “additional compile-time checks” (which sounds good to me).

# Not recommend: macros

defmodule Account.Guards do

defmacro is_private(first_name, email) do

quote do

not(is_nil(unquote(first_name))) and

not(unquote(email) == unquote(first_name))

end

end

end

# Recommended: defguard

defmodule Account.Guards do

defguard is_private(first_name, email) when not(is_nil(first_name)) and not(email == first_name)

end

Now we can add one more function clause to the top of our module to satisfy our PII requirement.

defmodule Account do

import Account.Guards, only: [is_private: 2]

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last, email: email}) when is_private(first, email) do

“<<Redacted>>”

end

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}) when not is_nil(first) do

String.trim("#{first} #{last}")

end

def display_name(%{username: username}) when not is_nil(username) do

"#{username}"

end

def display_name(_), do: "New User"

end

Wrap Up

Thanks to the power of pattern matching and multi-clause functions, we now have clear, clean, and effective code to handle displaying user names. And as new requirements come up, we don’t have to touch any of these existing methods. We can simply add new clauses as needed.

defmodule Account do

import Account.Guards, only: [is_private: 2]

# function heads only

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last, email: email}) when is_private(first, email)

def display_name(%{first: first, last: last}) when not is_nil(first)

def display_name(%{username: username}) when not is_nil(username)

def display_name(_)

end

Takeaways

As mentioned back at the beginning, working with pattern matching in Elixir requires you to think a bit differently - but different in a good way. The way the language is designed - the paradigms it embraces, the functionality it supports - encourages you to follow general programming best practices. Pattern matching is one of the best examples of this.

Take pattern matching on multi-clause functions. By supporting this, Elixir nudges you towards writing small, declarative functions - short functions that do one thing only, e.g. functions that follow the Single Responsibility Principle.

Likewise, by declaring the pattern you want to match against, you’re sending a clear signal about what inputs you expect to receive. Your code becomes more self-documenting by default.

Plus, since pattern matching is ubiqutious in the language, once you master this concept, you’re set up to master it all. It’s the perfect jumping off point for exploring all the other amazing things in Elixir built around this core concept, like GenServers, plug… the list goes on and on.

All-in-all, Elixir encourages you to write code that’s 1) declarative 2) self-documenting and 3) well scoped. It’s helping you become a stronger programmer, and it’s setting you up to become a true rockstar Elixir developer.

Now that’s impressive.

Any questions? Leave them in the comments below. Thanks for reading!

Want to work on a team that builds cool stuff in Elixir? My team is hiring!

And for examples of more cool stuff our team has built recently, check out our newly launched Data Science Bootcamp Prep course, featuring an Elixir-backed Jupyter notebook integration.

Resources

Readings:

- Elixir docs: Pattern Matching

- Elixir School: Pattern Matching

- Anna Neyzberg, “Pattern Matching in Elixir: Five Things to Remember”

Videos:

- Joao Goncalves, “Getting Started with Elixir: Pattern Matching versus Assignment”

- Dave Thomas, Think Different (ElixirConf2014 Keynote)

- Lance Halvorsen, “Confident Elixir” (ElixirConf 2015)

Tutorials:

- Code School, Try Elixir - Pattern Matching

Footnotes

[1] Binding vs. Assignment

The distinction between variable binding vs. variable assignment is small, but critical when it comes to pattern matching in Elixir. For any readers familiar with Erlang, all the binding and re-binding variables above may have seemed odd. In Erlang, variables are immutable, and since Elixir is built on top of the Erlang VM, variables are immutable in Elixir, too.

If variables are immutable, then why are we allowed to tie and re-tie values to variables with pattern matching?

We have to drop down to machine-level memory management to get the answer. Assignment assigns data to a place in memory, so re-assigning a variable changes the data in place. Binding creates a reference to a place in memory, so re-binding just changes the reference, not the data itself.

Think of the variable as a suitcase. Binding the variable is like slapping a label on the suitcase. Assigning is like swapping out the contents [source].

For more context, Elixir creator José Valim has a nice post on Comparing Elixir and Erlang variables.